Where Did the Reign of Terror Take Place

The Reign of Terror was a violent period of the French Revolution, beginning at some point in 1793 and continuing until the fall of Robespierre in mid-1794. Stories and images of the Reign of Terror have come to dominate our perceptions of the French Revolution.

Defining the Terror

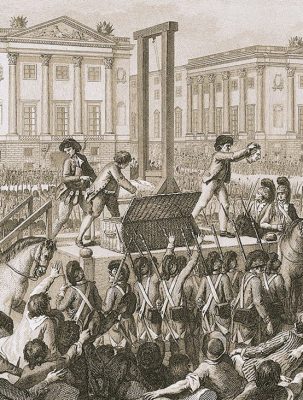

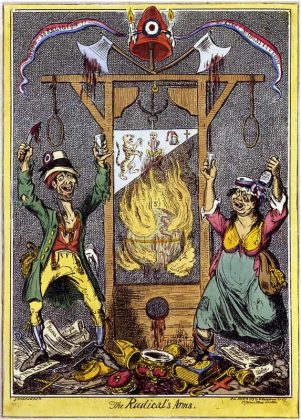

According to folklore, the Terror was a brief but deadly period where Maximilien Robespierre, the Committee of Public Safety and the Revolutionary Tribunals condemned thousands of people to die under the falling blade of the guillotine.

The realities of the Terror were more complex. The Reign of Terror was not driven by one man, one body or one policy. It was a child with many parents, triggered and driven by different forces and factors.

Whatever its causes, the Reign of Terror was certainly the most violent period of the French Revolution. Between the two summers of 1793 and 1794, more than 50,000 people were killed for suspected counter-revolutionary activity or so-called "crimes against liberty". One-third of this number died under the falling blade of the guillotine.

If the Convention's brutal retaliation against civilians in the Vendée and other rebellious provinces are included, the victims of the Terror number may closer to 250,000.

Why the Terror?

When and why the Reign of Terror began are matters of historical debate. For some historians, the Reign of Terror commenced with the execution of Louis XVI in January 1793. Others date it to the formation of the Revolutionary Tribunal (March 1793), the expulsion of Girondinist deputies from the National Convention (June 1793) or the murder of Jean-Paul Marat (July 1793).

If the Reign of Terror had a single legislative beginning, it was on September 5th 1793, the day when Montagnard deputies in the National Convention voiced a perceived need for counter-revolutionary terror.

Addressing the Convention, the radical Jacobin and Committee of Public Safety member Bertrand Barère summarised what was needed:

"Terror is the order of the day. This is how to do away instantly with both royalists and moderates and the restless, counter-revolutionary scum. The royalists want blood, well, they shall have the blood of the conspirators, the likes of Brissot and Marie Antoinette. It will be an operation for special Revolutionary Tribunals."

Fear and paranoia

These fears were driven by France's war with Europe, rumours of a foreign invasion and the treachery ofémigrés, spies and counter-revolutionaries.

This paranoid hysteria was particularly rife among Parisian radicals: the Jacobins and Cordeliers, the men of the sections and the sans culottes. Some of them attributed the economic suffering of the working classes to counter-revolutionary subterfuge and conspiracies. Together they urged the Convention to take tougher action against 'enemies of the revolution'.

From this wellspring of panic and suspicion came a year of state-sanctioned terror. Anyone accused or even suspected of counter-revolutionary activity could be targeted. Thousands of French citizens were denounced, given hasty trials devoid of fairness and due process, then sent either to prison or the 'national razor' (the guillotine).

Protecting the revolution

Those who initiated the Terror saw it as bitter but necessary medicine, a purge of reactionary elements so the revolution could survive and remain on course. Little new policy was needed to initiate a policy of terror. Speeches in the Convention set the tone, while the radicals in the Committee of Public Safety (CPS) gave their approval.

The Law of Suspects, passed in September 1793, formed the legislative basis for the Terror by outlining who might be targeted.

The Law of Suspects called for the immediate detention of anyone in one of six categories. Anything from hoarding grain, harbouring suspects, evading thelevée en masse (conscription), possessing subversive documents, even speaking critically of the government could lead to a charge.

Arrests and trials were conducted by the Revolutionary Tribunals, which were expanded and given new legal authorities.

Prominent victims

The Reign of Terror brought many lives, both prominent and otherwise, to a violent and inglorious end. Contrary to popular assumptions, only a small proportion of its victims died under the blade of the guillotine.

Among the Terror's more notable victims were the former queen Marie Antoinette; the Girondon orator Jacques Brissot; former Jacobin leader Antoine Barnave; Paris' first mayor Jean-Sylvain Bailly; prominent female revolutionaries Madame Roland and Olympe de Gouges; the former mistress of Louis XV, Madame du Barry; Charlotte Corday, the assassin of Jean-Paul Marat; Philippe Égalité, the former Duke of Orleans; the dead king's defence lawyer Guillaume Malesherbes; Antoine Lavoisier, one of France's most famous scientists; the radical sans culotte leader Jacques Hébert; the prominent journalist Camille Desmoulins; and the populist political leader Georges Danton.

Most victims of the Terror, however, remain faceless and unknown to history. Some were clergymen, nobles, conspirators and defenders of the old regime – but the vast majority were members of the Third Estate.

The momentum of Terror

Once started, the Reign of Terror developed its own momentum and became almost impossible to stop. Terror became the revolution, so opposing or criticising the Terror was itself a counter-revolutionary act. To speak negatively of the Terror was to volunteer oneself as a suspect.

The Reign of Terror could only escalate or collapse – and so it escalated. The man most responsible for this was not Robespierre but one of his allies, Georges Couthon.

A Clermont lawyer who once dedicated himself to representing the poor, Couthon was elected to the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention, where at first he sat with the Plain before gravitating to the Montagnards. He also served briefly as a military leader, overseeing the suppression of counter-revolutionary groups in Lyons before being struck down with an unknown form of paralysis.

Couthon was softly spoken, reserved to the point of timidity and seldom out of his wheelchair – but these qualities concealed a revolutionary heart that was no less ruthless than Robespierre's. Couthon was a man who would do anything to protect the revolution, whatever the eventual cost.

The 'Great Terror'

Frustrated by the inadequate pace of justice and Paris' overflowing prisons, Couthon acted. In early June, he introduced the Law of 22 Prairial, later dubbed the 'Law of the Great Terror', onto the floor of the National Convention. It was passed on June 10th 1794 with the backing of Robespierre and the CPS.

The Prairial law removed the National Convention's oversight over the Revolutionary Tribunals, expanding the power of the Tribunals and allowing them to act swiftly, autonomously and without review or appeal. Ordinary citizens could denounce suspects directly to the Tribunals, rather than reporting them to the police, the CPS or the Convention's other committees.

The Law of 22 Prairial changed the procedures of the Tribunals so that accused persons were left almost defenceless. Prior questioning or deposition of suspects was deemed "superfluous", allowing accused persons to be sent straight to trial. The cross-examination of witnesses was banned and only the prosecution was permitted to tender evidence. In some cases, juries could suspend a trial and hand down a verdict, even before all the evidence had been heard.

Significantly, the Law of 22 Prairial also required Revolutionary Tribunals to either acquit suspects or sentence them to death. Fines, imprisonment, discharge, parole and commutation were no longer available as sentencing options. Accused persons either walked free or were carted to the guillotine. Needless to say, this law produced a marked escalation in the number of executions.

The Prairial legislation came at a time when France's revolutionary army was beginning to assert itself on the battlefield and the foreign threat was dissipating, not increasing. But May 1794 was also marked by several conspiracies and assassination attempts, most notably against Robespierre. On May 20th, a former lottery worker named Henri Ladmirat set out to murder Robespierre but, unable to find him, fired pistol shots at another politician, Collot d'Herbois. According to one contemporary, Robespierre became obsessed with assassination plots and was "frightened that his own shadow would assassinate him".

Streets clogged with blood

Whatever their causes, the changes of 22 Prairial accelerated the wheels of the Terror. The period between June 10th and the fall of Robespierre on July 27th became known as the Great Terror.

During these seven weeks, almost 1,400 people were executed in Paris – around 200 more than in the previous 12 months. Executions had previously averaged around three a day; after 22 Prairial this increased tenfold. Suspects were tried, sentenced and executed in groups, often dozens at a time. Guillotinings were so frequent that the flagstones at the Place de la Révolution became clogged with blood and the whole square began to smell rancid.

The government responded by moving most executions to the site of the former Bastille, however the sans culottes there complained that this was disrupting business, so the guillotine was moved even further east. Crowds at executions began to dwindle, though it is unclear whether Parisians had become opposed to the Terror or just indifferent to guillotinings.

A historian's view:

"This notorious law [22 Prairial] created a murder machine… A good proportion of the accused were to be sent up by the six special commissions which were to process the dossiers of suspects. They were now to funnel unfortunate individuals, accused of the vaguest of crimes and convicted simply by administrative fiat, to a tribunal that could only acquit or punish with death… It is a commentary on the pervasive atmosphere of black suspicion that this law was seen as a solution."

Donald M. Sutherland

1. The Reign of Terror was the most violent phase of the French Revolution, a year-long period between the summers of 1793 and 1794. During this time around 50,000 French citizens were executed.

2. Historians are divided about the onset and causes of the Terror, however, the revolutionary war, fears of foreign invasion, rumours about counter-revolutionary activity, assassination plots and zealots in the government were all contributing factors.

3. The Reign of Terror was formally initiated in September 1793, when radical Montagnards rose and asserted that a period of terror and repression was needed to protect the revolution.

4. During the Terror, justice was distributed by the Revolutionary Tribunals, which were expanded and given new powers. This was particularly true after the Law of 22 Prairial, authored by Georges Couthon.

5. The seven-week period between June 10th and the fall of Robespierre on July 27th became known as the Great Terror. During this period the Revolutionary Tribunals abandoned many of their procedures and the daily rate of executions increased tenfold.

Citation information

Title: "The Reign of Terror"

Authors: Jennifer Llewellyn, Steve Thompson

Publisher: Alpha History

URL: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/reign-of-terror/

Date published: August 18, 2020

Date accessed: December 16, 2021

Copyright: The content on this page may not be republished without our express permission. For more information on usage, please refer to our Terms of Use.

Where Did the Reign of Terror Take Place

Source: https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/reign-of-terror/

0 Response to "Where Did the Reign of Terror Take Place"

Post a Comment